Building Spoken Language In The Classroom

written by Simon Day – Education and Oracy consultant

The COVID pandemic continues to result in increases in anxiety and depression in our young people as well as referrals for speech and language support.

In short, too many young people lack the spoken language and communication skills needed to contribute to society, democracy and the workplace. Little wonder that LinkedIn’s 2024 skills survey identified the most in-demand skills as collaboration, communication and leadership.

The acquisition of these skills begins in the classroom, as students are provided opportunities to explore, process and present themselves through talk. Providing a talk-rich environment enables students to:

· Develop more meaningful working relationships with teachers and their peers

· Build self-confidence and emotional intelligence

· Generate and process ideas in preparation for writing

As James Britton once said: “Reading and writing float on a sea of talk.” We all want students to succeed in exams and employability, but it starts with developing good oracy.

Think, Pair, Share

In a world where everything is expected to be on-demand or even instantaneous, we can erroneously apply the same impatient approach to successful thinking. However, the process is far more complex and needs sufficient time – more than the average 0.9 seconds a typical teacher gives between posing a question and demanding an answer.

Careful framing is needed to give students time to think meaningfully. Not only is the time important, but environmental stimuli also need to be carefully managed. As Willingam explains, “Successful thinking relies on four factors: information from the environment, facts in long-term memory, procedures in long-term memory, and the amount of space in working memory (2010, p.18).’

Gaps in prior knowledge, noise on the corridor, the lawnmower outside, distractions within the room, ambiguous instructions and a plethora of external factors can disrupt and undermine thinking. Creating a climate for effective thinking is more than half the battle.

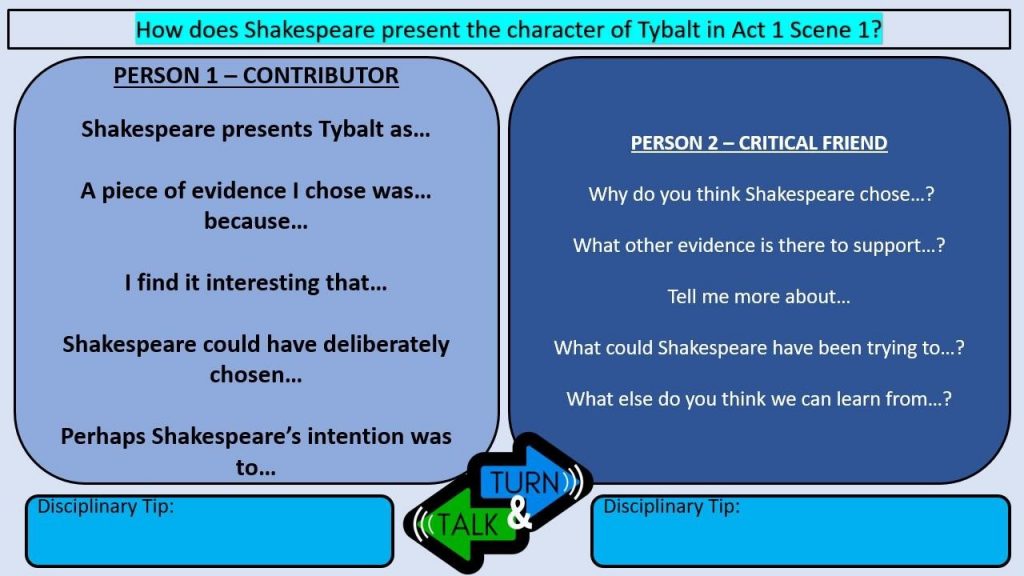

The Partnership for 21st Century Skills has identified communication as one of four key competencies for life-learning and innovation. Creating a structured, purposeful channel for students to engage in natural, dialogic talk is critical. Through two roles, those of the ‘contributor’, and the ‘critical friend’, students can explore key topics and questions in a courageous way, heavily supported by the subject specialist at first before gradually moving towards independent, disciplinary interrogation. The conversation between the ‘contributor’ and the ‘critical friend’ will also be metacognitive in nature, supporting the contributor to reflect, self-regulate and improve their oracy.

Note this example from a Year 7 English lesson. The question at the top will eventually be an extended written response. The teacher could stand at the front, trying fruitlessly to probe for a minutely specific, highly complex response, or they can create an environment in which students can draw these answers out of each other.

The students are provided the core question and an appropriate window of time to generate their ideas, in silence, on whiteboards. Instructions are front-loaded, with the means of participation being issued before the question so attention is not split.

Following the silent window, students are instructed to turn and face each other, deciding who will be the ‘contributor’ and who will be the ‘critical friend’. An appropriate window of time is then provided for students to fulfil both roles, swapping half-way through. Prompts like those seen in the image, with additional key words if desired, can be used to help students frame and deepen their responses. These sentence stems allow students to speak in a similar vein to what their eventual written response will be, thereby preparing them for writing.

This strategy allows students to formally articulate their ideas and be appropriately challenged by their peer. This externalisation process, in both writing on a whiteboard and then speaking their ideas aloud, prepares students to contribute to a whole-class level discussion, empowered to contribute meaningfully as the thinking process has been carefully managed. A study in the Journal of Psychology and Education concludes: “exchanging ideas with a partner is an essential condition to foster elaboration of ideas and confidence in sharing them in class.”

Whilst this technique has been used in classrooms for decades, an understanding of the thinking required and how to set up the task for effective oracy and processing of ideas will help students prepare for writing and develop the skills they will need for life beyond school.

Simon Day

You can find out more about our Teacher CPD here or get in touch to arrange a meeting with Talk The Talk to discuss your CPD objectives here

Categories: Uncategorised

Tags: employability, essential skills, oracy